Some of the first adorable patients to trickle into Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’s pediatric clinic when it opened in 2007—long before she was named the first surgeon general of California—were referred by teachers and principals.

Sitting in her examination rooms back then, in one of San Francisco’s poorest neighborhoods, Burke Harris knew almost immediately that something was amiss. Her young patients arrived with tentative diagnoses of oppositional defiant disorder or learning deficits, but routine exams uncovered a host of more serious physical ailments: asthma, autoimmune hepatitis, and even growth failure. Almost inevitably, the children’s caretakers—also sick with advanced diabetes, heart disease, or cancer—relayed harrowing stories of family incarceration, sexual abuse, and even murder.

“I’d have this snapshot of multigenerational adversity in one room,” Burke Harris said, still looking worried decades later. How did the pieces fit together? What did a learning problem have to do with asthma, or with exposure to trauma? Could any of it be connected to terminal conditions like cancer?

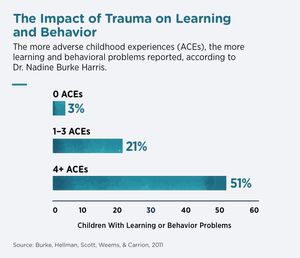

An answer arrived “like a bolt of lightning” in 2008, when Burke Harris read a seminal study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) linking childhood trauma—which the researchers called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—to dramatically higher rates of heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes in middle-aged patients. Burke Harris’s own groundbreaking research in 2011completed the picture, revealing an astonishing relationship between childhood trauma and the onset of learning and behavioral issues.

Today, the implications of those insights still feel revolutionary, blowing a hole in pious American myths about equity, social mobility, and financial success. Our good fortune, or rotten luck, is “written into our biology,” Burke Harris asserts in her 2018 book, The Deepest Well—wired into synapses and coiled within strands of DNA—where it exerts a stealthy and persistent influence on our bodies and minds, for better or worse.

For children with ACEs, the damage is reversible, and teachers can help, Burke Harris says—but she’s adamant that they can’t do it alone. “We all have to play our positions,” she insists, emphasizing the need for broader coordination between medical, educational, and emergency systems. “It’s unfair to ask teachers to be therapists or doctors. The role of educators is in delivering that daily dose of buffering care that’s so important for healing.”

I sat down with Burke Harris recently to talk about how she came to her vocation, whether our traditional school disciplinary policies are supported by science, and how she overcame her skepticism about meditation.

STEPHEN MERRILL: In your book The Deepest Well, you say your father taught you that “there is a molecular mechanism behind every natural phenomenon.” There’s just such a deep curiosity about how the world works running through the book.

NADINE BURKE HARRIS: Yeah. That is just part of my DNA. It’s the way that I was raised—my dad is an organic chemist. When we were little kids—when my four brothers and I were throwing paper airplanes at each other—your typical parent would be like, “Stop that or else you’ll put an eye out.”

My dad would come in and he would say, “OK, let’s time your throws. Then let’s measure the distance so we can calculate the velocity. Then we know that gravity is 9.8 meters per second squared, so we can calculate the lift under the wings.” It was science all day, every day in my house.

MERRILL: Right, and on one level the book reads like a scientific mystery. At your clinic, you’re surrounded by kids with really serious illnesses—but for years the “molecular mechanism” beneath them eludes you. Can you take me back to that moment in 2008 when you were handed the CDC’s study on ACEs? What were you feeling when you read that?

BURKE HARRIS: It was like being hit with a bolt of lightning. You remember in that movie The Matrix, when all of a sudden Neo can see what the universe is really made out of? It was just such a validation—a coming together of all of these disparate pieces—that I feel I had been seeing throughout my career.

Keep in mind, I had done research in college about the effects of stress hormones like cortisol and how they affect development. And I had been—day in, day out—caring for patients at Bayview Hunters Point clinic, hearing their stories and seeing over and over again how they were impacted by the harms of poverty, trauma, and adversity.

Almost every cell in your body has a receptor for cortisol. When the stress response is triggered too frequently, or too severely, it can change the structure and function of children’s developing brains, their immune and hormonal systems—and even the way their DNA is read and transcribed. Those changes are what we now refer to as a toxic stress response.

MERRILL: You’ve said that school-aged children with ACEs often present with oppositional defiant disorder, impulse control issues, or difficulty focusing. What can teachers do? Does the science support social and emotional learning (SEL)?

BURKE HARRIS: Absolutely. Those are the tools to help kids understand how to recognize and regulate their emotions and their behaviors. One of the things that I think is really crucial: As a doctor, I may be the one who’s screening for ACEs, but I might see the child at the most a couple of times a year.

Educators can deliver the daily doses of healing interactions that truly are the antidote to toxic stress. And just as the science shows that it’s the cumulative dose of early adversity that’s most harmful, it also shows that the cumulative dose of healing nurturing interactions is most healing.

Giving children the tools to understand how to recognize what’s going on with them, then how to respond—especially to be able to calm their bodies down—truly is healing.

In her 2011 study, Burke Harris found a powerful link between the number of childhood ACEs and the onset of learning and behavioral issues.

MERRILL: I think our teachers will be glad to hear it.

BURKE HARRIS: I cannot tell you the number of kids that I have cared for who, when I say to them, “You know what? Because of what you’ve experienced, your body might be making more stress hormones than it should. That can look and feel like being quick to anger, or having trouble controlling your impulses, or getting sick easily”—I can’t tell you the number of kids who have looked at me and literally said, “Oh, you mean I’m not crazy?”

Many of our kids have been told that they are the problem. Helping them to understand that what’s going on in their bodies is actually a normal response to the abnormal circumstance that they find themselves in, giving them tools to understand how to calm themselves down, how to keep themselves safe, how to connect with nurturing relationships—I’ve seen it be life-changing and life-saving.

MERRILL: Have you given thought to whether our discipline policies in schools are informed by science? Are punitive tactics like loss of recess, shaming, expulsion, suspension—are those going to work for kids with trauma?

BURKE HARRIS: I have a feeling that is a setup, but I’m grateful for it [laughs]. Because that’s really the whole point. If the science shows us that many of these behaviors are associated with a toxic stress response, then blaming and shaming that child is not going to improve that.

For example, if you have a child who is experiencing adversity at home and is being defiant, acting out, having a terrible time with impulse control, suspending them so that they can go home to be in that environment may be doing more harm than good.

We obviously need school safety policies and policies that support the orderly functioning of the school environment. But the science suggests that those should be things like in-school suspensions, restorative justice, opportunities to de-escalate and give a child the time and space to allow their adrenaline and cortisol levels to come down. It could be as simple as 15 minutes in a quiet area to get back to self-regulation. That’s a way to work with a child’s biology instead of working against the child’s biology.

MERRILL: That reminds me of this school in Nashville where I first saw a peace corner. Have you heard of these? Kids can go there just to calm down. There are even activities to get them to self-regulate.

BURKE HARRIS: Yes, I’ve seen that! There’s one in California that has a similar space—it’s beautiful. I think it was in Fresno. When I saw it I was just like, “This is awesome. This is science being implemented in our classrooms.”

MERRILL: Can you talk to me about meditation? I know you were a little wary of the practice at first, but now you seem to prescribe it.

BURKE HARRIS: Yeah. That’s no joke—I really do prescribe it as part of my clinical practice. If you are experiencing an overactive stress response, there’s cortisol, adrenaline, all these stress hormones—those are what leads to long-term harm.

So I went through the literature and said, “OK, well, what does the opposite?” I was skeptical at first, but meditation helps to regulate the part of the brain that is associated with recovery post-provocation; it’s associated with reduced levels of cortisol and other stress hormones; and it also reduces the physiological indicators of an active stress response, like blood pressure and heart rate.

So I implemented a program in my clinical practice—we taught mindfulness as part of our treatment protocol for kids with toxic stress.

MERRILL: How young can the kids start?

BURKE HARRIS: Mindfulness practices can be done itty-bitty, for kids as young as 3 in my practice. The modality might change a little bit depending on the developmental stage. From 3 to 6, you might do one type. Then as kids get older, you can do more things, like downloading a mindfulness app on your phone and practicing 10 or 20 minutes a day.

MERRILL: Is there anything else you want to say? Anything I missed?

BURKE HARRIS: The last thing that I want to say—especially in light of Covid and all of the anxiety around that issue—is for our educators. We know that educators are the backbone of our society. As we do this work, I want to encourage you to put your own oxygen mask on first. Because we need you in this fight. We need you in this struggle.

In order for any of us to provide that safe, stable, and nurturing environment for the children that we serve, we have to practice self-care so that we can be available. Please make sure to put your own oxygen mask on and practice real care for yourself so that you can be there for the next generation.

Trauma is ‘Written Into Our Bodies’—but Educators Can Help by Stephen Merrill was originally published on September 11, 2020 at Edutopia.

Most people wonder how to get their feet off the floor. The first way IS to pour as much of your body weight into your hands as

Most people wonder how to get their feet off the floor. The first way IS to pour as much of your body weight into your hands as

You must be logged in to post a comment.